Media and Society

Production, Content and Participation

Student Resources

Meaning, Representation and Power

Chapter Introduction

The creation and control of meaning-making is critical to the exercise of power.

How is meaning made and controlled?

How does representation work as a social process?

How is meaning used to exercise power?

In this chapter we:

- Define meaning and power.

- Consider how meaning and power are related to one another.

- Examine several fundamental accounts of the relationship between meaning and power: hegemony, ideology, discourse and representation.

- Overview how media representations organise everyday life.

Cases & Activities

Constructing meanings: #iftheygunnedmedown

The shooting of Mike Brown, an unarmed black teenager, by police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014 drew attention to how news organisations draw on social media profiles to depict victims or perpetrators of crime.

Some news organisations ran a photo of Brown in his graduation cap and gown, while many others used a photo of Brown wearing a basketball singlet and making a hand gesture that naïve viewers might interpret as a gang sign.

The use of an image that implied Brown was a member of a gang, prompted many black Americans to post contrasting images from their social media accounts to Twitter using the hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown. Many featured young black men in formal dress for church, military or graduation in one image, while in the other image they wore street wear that could be used to suggest they are gang members.

Like the images used for Brown, people drew attention to the way that selective use of images from their social media profiles could be used to construct very different representations of their identities. By constructing their identity one way or another the media could invoke differing perceptions of the extent to which the use of force by police was legitimate.

Consider these images. How do the two images of the same individual represent them in different ways? What ‘symbols’ in the images convey different meanings that you associate with that individual? How do the images position the individuals differently in power relationships?

Examine images of yourself on your own social media profile. Find two contrasting images. Consider the way in which the images represent your identity differently. If the media were reporting, could they use the images to tell different stories about your character? Would characteristics like your gender, ethnicity or sexuality be at play in the interpretation of those images? If not, would the images suggest different aspects of your character that might affect your reputation.

Links

Links below to news stories about the #iftheygunnedmedown hashtag.

http://www.buzzfeed.com/mrloganrhoades/how-the-powerful-iftheygunnedmedown-movement-changed-the-con

http://mashable.com/2014/08/12/iftheygunnedmedown-hashtag/

http://time.com/3100975/iftheygunnedmedown-ferguson-missouri-michael-brown/

Representation as a social process: The Occupy protests and casually-pepper-spray-everything cop meme

Representation is a social system involving the continuous production and circulation of meaning. People interact with each other to represent events. Media representations work inter-textually. That is, meanings are transferred from one text to another. Texts make new arrangements of meanings that often depend on the capacity of readers to ‘decode’ them by understanding them in relation to other texts.

Internet memes demonstrate the inter-textual and social process of representation in action.

The first image above is an image from a protest at the University of California (Davis) in 2011. The protest was part of the global Occupy movement. When students refused to disband a campus police officer sprayed them with pepper spray. The cop’s act was a ‘violent’ one. As an authority figure he used physical force against people. The police are licensed to do that by the state and the university. The act though is also a symbolic one. When police use force against citizens they demonstrate to them what will happen if they do not obey the law.

The cop’s act set off a change of events where the student protestors, university management, news organisations, and the public interacted with each other in an effort to represent the event in different ways.

The protest was videoed and uploaded to YouTube. In the video the crowd can be heard chanting ‘the whole world is watching’ as the cop sprays the protestors with pepper spray. The protestors captured the act on camera. The protestors understood that they could use video to ‘bear witness’ to the event. In doing so, they were able to ‘re-present’ it. They take the act from its original context and turn it into a media text. That text then circulated rapidly through social networks. The ‘re-presentation’ of the act symbolises the excessive use of force by the powerful. The Occupy protests aimed to represent the ‘99%’ of ordinary people against the world’s privileged ‘1%’. The representation of the cop pepper-spraying the protestors symbolises – ‘stands in’ for – the entrenched privilege and blatant use of power the Occupy movement as protesting against in its slogan ‘we are the 99%’.

The protestors’ videos of the incident became a news story. The university needed to respond to the way the video of the protest represented the institution and its relationship with students. The Chancellor of the university organised a media conference. This was an attempt to ‘counter’ the meanings and narratives circulating in conjunction with the pepper spray video. The university attempted to control how the event was represented. They did that by inviting selected media organisations to the media conference, and excluding students from the venue. The students responded to being excluded by forming a silent protest outside. When the Chancellor eventually emerged they formed a silent guard all the way from the venue to her car. This silent protest was also filmed and the video circulated widely online. The protestors used silence to represent their exclusion. In doing so they drew attention to how the powerful maintain power by controlling who speaks where and when, by attempting to control who gets to represent events. When the Chancellor excluded students from the press conference, she attempted to work with the police and media organisations to control how the event was represented.

Following this event, images of the cop pepper-spraying students were widely reappropriated and recirculated. The pepper-spraying cop ‘represented’ the use of excessive force, the attempt of the powerful to control who gets to speak, the disrespect for democratic values. The cop more broadly represented the use of force against ordinary people, the undermining of democratic rights, and the policing of public space.

The powerful – like the chancellor and the police – use strategies to attempt to control media representations. They use their relations with media, their resources to organise media events, and control who gets access to those events. In contrast, ordinary people use tacts to resist those meanings.

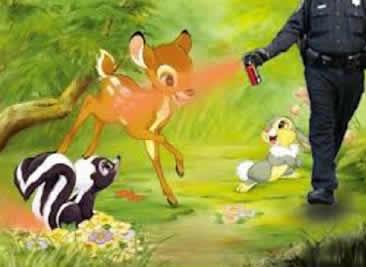

One way this unfolded with the pepper spray cop was by using the cop as a symbol of excessive power and ‘remixing’ his image into other popular culture texts. The image of the cop worked intertextually to create new representations. In the image above the cop pepper-sprays Bambi. To make sense of this image we need to understand both texts it references: the pepper spray cop and the film Bambi. In the image above, the cop is crudely superimposed over a scene from Bambi. In doing so, the innocence of the scene from Bambi evident in the joyful expressions on the characters’ faces and the colourful animation is juxtaposed with the dark, menacing and violent presence of the cop. The cop is larger than the characters from the animation, towering over them and his head is cropped out of the frame, as if to make him a faceless and distant figure. This image is one of many examples where the cop was super-imposed onto another scene – a movie like Bambi, an important historical moment like the Declaration of Independence, or a cultural icon like a Renaissance painting. The creators of these images were able to repeat this juxtaposition by ‘photo-shopping’ the cop over images in this way. Meaning is created via the repeated gesture of imposing the cop in scenes that evoked the innocence of childhood memory or shared cultural history and values. We can see throughout this example how representation works as a social process, constructing how we understand and act in the world, and a process in which some people have more power than others.

Map out the array of actors involved in attempting to represent the student protest at UC Davis. What were their preferred representations of the event and why? What resources and techniques did they use to create their preferred representations? Who did they interact with to create their preferred representations?

Find other examples of the pepper-spray cop meme.

What texts are referenced in the memes?

How is meaning created in the interplay between the texts?

What do the texts represent?

Links

Links below to the Casually-Pepper-Spray-Everything Cop meme.

Know Your Meme offers a history and explanation of the meme.

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/casually-pepper-spray-everything-cop

Google image search for the meme.

Student video of the protest where the cop pepper-sprays students.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VBntXr1QFnU

News report about the pepper spray incident.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XCJEomwVMrw

Video of students’ silent protest.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nmfIuKelOt4

Fox News description of pepper spray as a ‘food product’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qrx6DDgTH_w

Changing meanings

Consider the major societies and ideologies since the beginning of the twentieth century:

- Communism

- Social Democracy

- Liberalism

- Nationalism

- Conservatism

- Fascism

Consider discourses that some of these societies used to organise social and political systems:

- Imperialism: empires can organise development, trade and governance more effectively than indigenous populations.

- Decolonisation: Empires are bad. Indigenous populations should be given independence.

- Human rights: There are universal human values that all societies should respect.

Each of these ideologies was or is taken to be ‘common-sense’. Examine one or more and ask:

- What ideas did they take to be ‘common-sense’ and ‘natural’?

- What institutions, practices, rituals, words and images did they use to convey their ideas?

- Who conveyed the ideas?

- Whose interests did these common-sense ideas serve?

- Who opposed these ideas and why?

- Are these ideas still common-sense? If not, what happened?

Explaining representation with The Wire

In a famous scene in the television drama The Wire three members of a drug gang sit guarding territory called ‘the Pit’ in an inner-city housing estate. The scene uses a metaphor to create meaning between everyday experience, mental concepts and a shared language. The scene illustrates the social nature of representation, how it is embedded within our everyday lives and relationships, and how it embodies and mediates power relationships.

D’Angelo, the leader of the trio sees the two junior members – Wallace and Bodie – playing checkers on a chess board. ‘Hold up you to don’t know how to play chess do you?’ he asks, and sits down to teach them the rules. He begins by picking up the king.

D’Angelo: See this? This the kingpin, a’ight? And he the man. You get the other dude’s king, you got the game. But he trying to get your king too, so you gotta protect it. Now, the king, he move one space any direction he damn choose, ’cause he’s the king. Like this, this, this, a’ight? But he ain’t got no hustle. But the rest of these motherfuckers on the team, they got his back. And they run so deep, he really ain’t gotta do shit.

Bodie: Like your uncle.

D’Angelo: Yeah, like my uncle. You see this? This the queen. She smart, she fast. She move any way she want, as far as she want. And she is the go-get-shit-done piece.

Wallace: Remind me of Stringer.

D’Angelo: And this over here is the castle. It’s like the stash. It can move like this, and like this.

Wallace: Dog, stash don’t move, man.

D’Angelo: C’mon, yo, think. How many time we move the stash house this week? Right? And every time we move the stash, we gotta move a little muscle with it, right? To protect it.

Bodie: True, true, you right. All right, what about them little baldheaded bitches right there?

D’Angelo: These right here, these are the pawns. They like the soldiers. They move like this, one space forward only. Except when they fight, then it’s like this. And they like the front lines, they be out in the field.

Wallace: So how do you get to be the king?

D’Angelo: It ain’t like that. See, the king stay the king, a’ight? Everything stay who he is. Except for the pawns. Now, if the pawn make it all the way down to the other dude’s side, he get to be queen. And like I said, the queen ain’t no bitch. She got all the moves.

Bodie: A’ight, so if I make it to the other end, I win.

D’Angelo: If you catch the other dude’s king and trap it, then you win.

Bodie: A’ight, but if I make it to the end, I’m top dog.

D’Angelo: Nah, yo, it ain’t like that. Look, the pawns, man, in the game, they get capped quick. They be out the game early.

Bodie: Unless they some smart-ass pawns.

D’Angelo explains the rules of chess drawing on the shared conceptual map and language of the inner-city drug trade. In his analysis of the scene, Peter Honig writes:

D’Angelo uses the familiar world of the drug hierarchy to explain an alien and complex game to Bodie and Wallace. At the same time, (the writers) use this scene to explain the (presumably) alien drug game to their audience using the (presumably) familiar rules of chess.

The rules of chess are understood via the world the characters live in, and the rules of the drug trade are understood via the world the audience lives in. Representation maintains power relationships by creating ways of understanding them. Representations make themselves true, ‘all knowledge, once applied in the real world, has real effects, and in that sense at least, ‘becomes true’’ (Hall 1997: 49). We are not outside representations. They constitute us as much as we produce and relate to them. Our representations shape both how we understand the world and how we act in it. They construct a position for us as the ‘reader’ or ‘viewer’, and we work to locate ourselves in relation to them. Representation is the production of social knowledge and therefore the development and maintenance of power relationships. Our way of understanding ourselves, our lives and our material worlds is marked out in relation to others, some of whom have more power to structure the schemas within which we understand the world.

By explaining the rules of chess to his colleagues D’Angelo is marking out the power relationships of the inner-city drug trade. For Honig,

D’Angelo isn’t so much teaching them how to play chess as he is trying to help them see that the world they are in is far more complex than they realise. But they refuse to see it, or at least Bodie does. His questions about promotion show a fundamental misunderstanding of board games, and all games. He keeps using the word ‘I’, as in a single piece standing in as his avatar. He is only capable of seeing the drug game as it applies to him in his limited experience in the Pit. He fails to consider the fact that a chess player has to manage an entire army of pieces with a variety of skills and abilities. The concept of both chess and the drug game are bigger than he realises.

The scene demonstrates how representation is a system that can communicate simple material aspects of the world like the rules of a game involving moving objects around a board. At the same time, it can also communicate complex, immaterial, social aspects of the world like the power relationships between people in a criminal enterprise. But, even though D’Angelo intends to explain those more complex power relationships, that doesn’t mean that Wallace and Bodie will understand. Representing social relationships always depends on our place within those relationships. D’Angelo’s explanation of how chess works is grounded in the everyday life experience of the inner-city drug trade, but even so the more junior members of the gang fail to fully appreciate the power relationships D’Angelo describes because of their position in the power relationships D’Angelo is representing. Much later in the narrative, Bodie appears to develop a fuller appreciation of D’Angelo’s representation when he says to a cop, ‘this game is rigged, we’re like them little bitches on the chess board’. The ability to make sense of representations is interrelated with our life experiences. The kind of life we lead, the people we interact with, the material environment we live in embeds us within certain systems of representation. Representation is a system for understanding things we can’t see or touch, but which we know shape our lives. Representation is critical to creating and regulating relationships between people. And, the material world in which we live shapes our systems of representation.

Bodie’s final line might also demonstrate the on-going nature of representation. Meanings are only ever partially and temporarily fixed. On one level the ‘rules’ of the game are represented as fixed and immutable to the ‘players’. The ‘king stays the king’ in both the game of chess and the drug trade. But, when Bodie says, ‘unless they some smart-ass pawns’, he suggests that players understand social arrangements and their meanings are never completely fixed. Regardless of whether we think D’Angelo ‘gets’ the bigger game that his junior colleagues don’t, or whether we think Bodie deftly ‘gets’ the contingent nature of meaning and power, what we do see here is how an explanation of the game of chess is used to re-present the inner-city drug trade and its power relationships. An explanation of the rules of chess serves to hold ‘in place relationships between people and the world’, and both the characters and the audience locate themselves in relation to those representations and perhaps recognise that they are never ‘finally fixed’ (Hall 1997: 23). Representation always involves the active participation of senders and receivers, communication must be understood as a process of exchange between people.

Representations are important for creating, enacting, maintaining and understanding relations of power. They help us to consider how power is something continually ‘done’ via communication. Practices of representation and power are diffused into our everyday lives and relations with people. Representation is a process embedded within the world, as much as it is a reflection of events and relationships in the world. Representation creates reality in the sense that by constructing our view of the world it shapes how we act in the world. These relationships are enacted by people at all positions in social hierarchies and formations. The three drug gang members as much as they ‘understand’ the system of representation D’Angelo explains to them, also enact it in their daily lives and practices. We can only understand the world and our place in it via discourse (Hall 1997: 45). For Foucault, this representational system was a ‘discursive formation’ that constructed and regulated ways of talking about topics. The relationship between media and the social world is a dynamic one, each interrelating with the other. Just as media re-presents the social world to us, in doing so, it shapes that world. Practices of representation are always-already embedded in the social world. They don’t sit outside of or above events and relationships. They are instead a part of them, and therefore condition them.

Map out how the game of chess represents the power relationships between characters in the urban drug trade.

Reflect on the extent to which the characters understand their role in those power relationships.

Consider how the game of chess makes the drug trade sensible to the audience. What meanings about the drug trade are conferred by the game of chess? Does the scene naturalise and legitimize the drug trade and the underclass?

The ‘King Stay the King’ scene from The Wire (Season 1, Episode 3).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0mxz2-AQ64

Peter Honig’s blogs about The Wire.

http://www.thewireblog.net/season-1/episode3_thebuys/chess-as-a-metaphor-for-everything/

Further Readings

The work of Stuart Hall and Nick Couldry are both instructive in developing an account of media representation. Stuart Hall’s Encoding/Decoding essay, originally published in 1973, provides a seminal account of the process by which meanings are inscribed into texts and deciphered by audiences. Hall’s book Representation published with several colleagues in 1997 (and in an updated edition in 2013) provides a clear and accessible explanation of the cultural and media processes of representation. In the past decade Nick Couldry’s work on mediatisation, media power and rituals has further advanced our understanding of media representations within a media-dense society. Couldry draws our attention to how practices of media representation are embedded in everyday cultural practices, social spaces and power relationships. In chapter 1 we also referred to Foucault’s notion of discourse. For more advanced readers his book Discipline and Punish is a good place to start. In that book he defines the relationship between power, knowledge and representation.

Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in television discourse (Vol. 7). Centre for Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham or Hall, S. (1991). Culture, media, language: working papers in cultural studies, 1972-79. Routledge: London.

Hall, S., Evans, J. & Nixon, S. (Ed.). (2013). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage: London.

Couldry, N. (2002). The place of media power: Pilgrims and witnesses of the media age. Routledge: London.

Couldry, N. (2003). Media rituals: A critical approach. Routledge: London

Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2013). Conceptualizing mediatization: Contexts, traditions, arguments. Communication Theory, 23(3), 191-202.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish. Penguin: London.