The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guide to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University

Student Resources

Diagnostic Toolkit

Diagnostic Toolkit: Score yourself from the diagnostic test in each chapter of the book, so you can identify your strengths and weaknesses and can plan your own, personal plan to build up your academic skills.

Find the answers to the tasks in each chapter below:

Chapter 1: Understanding University Culture

How confident are you that you are ready for your new life in Higher Education?

Check your score:

- 8–16: Your overall confidence level is low. You may be worried about your knowledge of university life and what you will be required to do in your studies. But don’t worry, many students feel like this when they start out on their academic journey. You will find that you soon become familiar with the demands and expectations of higher education, and your confidence and competence levels will improve quickly. It is excellent that you are aware of your concerns and you are ready to address these, and this book will help you do just that. We recommend that you work through each chapter systematically to maximise your skills development and build a solid foundation for your academic studies. You should pay particular attention to this chapter now, so that your knowledge and understanding of the systems and language of higher education become clear and help build your confidence levels in different areas of your studies. You should revisit this diagnostic as your studies progress to check your knowledge and awareness of your university’s systems and expectations.

- 17–28: Your overall confidence level is moderate. You may already be familiar with some academic systems and approaches to teaching and learning, and perhaps feel reasonably confident about some areas and aspects of your studies. We recommend that you work through the chapter systematically, as you may need to build on your knowledge and refresh your skills as you go along. You should also work through all other chapters in the book, in order to develop and further enhance your confidence and improve your performance. Don’t forget to re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development, and re-visit sections that are relevant to your immediate needs.

- 29–40: Your confidence level is high to amazingly high! This may be because you have already developed good awareness and knowledge of your university and its approach to teaching and learning. However, you should be aware that your confidence level might change when you begin your studies and you discover that your perceived knowledge and skills level does not match your real-world abilities. We recommend that you go through the book and cherry pick the chapters, sections and tasks that you feel are most relevant to your needs, but we also recommend that you re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development and overall confidence levels, and regularly review relevant sections in the book, as your university career progresses.

Chapter 2: Reading and Note-taking Skills

Which of the following best describes your approach to reading and note-taking?

If you ticked any of these statements, then there are ways for you to improve your reading. This may surprise you, as some of the above may look like good reading habits. Think carefully about balancing your available reading time and being efficient in locating resources. The answer isn’t always to read everything. This chapter will help you find and use the right sources effectively, without wasting your time.

Chapter 3: Getting the Most out of Lectures

The key points are highlighted in the transcript below.

What English do you speak?

So we need to think about why has English become the global language.

There are three main reasons for this. Firstly there has been military power associated with English speaking countries for the last 200 years. And also, Britain at the beginning of the 19th century was the world’s leading industrial and trading country. And then more recently, at the beginning of the 20th century, the U.S. economy was the fastest growing in the world. So those three things have contributed to English being the one that is now considered the global international language. So we can summarise that by saying that the spread of English has been mainly because of military power, industrial and trading influence, and economic strength.

So now if we think about all the people in the world who speak English, and we’ve already talked about the numbers of those who use it as their first language, second language, foreign language and so on, Linguists like to categorise the people who speak English and they’ve come up traditionally with using country and history as a way to categorise speakers of English. And we have these three terms, ENL, ESL and EFL.

So ENL or English as a Native Language. And the countries that have English as their native language have this because of the first diaspora of people from the British Isles in history. So basically, there was migration of people from England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales who went to North America in the 17th century – and I’m not going to go into the history of that now, with Pilgrim Fathers and so on. And then we have Australia and New Zealand, a bit later in the 18th century, and also South Africa in the mid-19th century. So this is related to history and these countries are known as countries with English as a native language.

And then if we think about ESL. ESL stands for English as a second language. And these countries are categorised because they were the result of the second diaspora, which is colonisation and colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And this is mainly Africa and before that Asia. So countries like India in Asia and Kenya in Africa.

And then EFL, which is English as a Foreign Language, i.e. those people from countries where English is not used within their country institutionally because they were not colonised.

This categorisation however is not straightforward. It doesn’t really work. So if we take an example. For example, India. India would be categorised as ESL, a country that has English as a second language due to having been colonised by the British and being part of the British Empire. But it’s not black and white because in India there are many users of English who have English as their first language not their second language so how can you call India an ESL country when some Indians have English as their first language.

So another example is Denmark. And Denmark is categorised in this system as an EFL country. It’s never been colonised and so is considered an EFL nation. But actually, the government of Denmark have had discussions about possibly making English their official second language. And some large Danish companies use English as their first language within the company even though their head office is in Denmark. The reason they do that is that they say it is a matter of being qualified for the globalised market and if companies have English as their first language they will be able to operate more effectively in the world economy.

I have a good quote here because there’s a problem of using ‘proficiency of English’ as the guide. If you are saying that first language users of English have better English than second language speakers, then that’s a problem because many native speakers are less proficient than some second language users. And I have this great quote from an American who lives in Denmark and he is a blogger. And on his blog he wrote and I quote,

“Every day I become more and more impressed when speaking with a Dane in English. Heck, they speak better English than some of my buddies back home, no offense guys.” So it’s a complex thing and categorising English speakers is something linguists want to do but doesn’t really work in a nice and neat, black and white way.

OK, so let’s move on now to thinking about the spread of English…

The diagnostic highlights that it is difficult to take effective notes if you haven’t prepared. Preparation will help you focus on the key elements of the talk and the key parts you will need to take away.

After any lecture, you need to re-visit your notes, make sure you understand them, and add detail.

Chapter 4: Communicating in Seminars

Are you ready for a seminar?

How did you score?

- More than 45: Your confidence levels are high! You’re ready to take on a seminar, but you can still make sure you’ve prepared beforehand, so don’t miss this chapter.

- 30–44: You’re clearly able to participate in seminars, but there’s still room for improvement. This chapter will help you be fully prepared so you can get the most out of seminars.

- 20–29: There’s nothing to worry about! You can make some contributions in seminars, but the advice for being prepared in this chapter will help you boost your participation.

- Less than 20: If you don’t feel confident participating in seminars yet, you’re not alone! Make sure you pay close attention to this chapter, which will help you prepare for a seminar so you can get the most out of it.

Chapter 5: Getting the Most out of Blended Learning Approach

How sure are you about the method of teaching on your chosen course at your institution?

How did you score?

- More than 20: Your confidence levels are high! You’re ready to take on your university’s blended learning approach, but you can still make sure you’ve prepared beforehand, so don’t miss this chapter.

- 15–19: You’re clearly well prepared for your university’s approach to teaching and learning , but there’s still room to gain more confidence. This chapter will help you be fully prepared so you can get the most out of the different approaches to teaching and learning.

- 10–14: There’s nothing to worry about! You clearly know about some aspects of your course, but the advice for being prepared in this chapter will help you boost your participation.

- Less than 10: If you don’t feel confident about the teaching and learning approach being used on your course yet, you’re not alone! Make sure you pay close attention to this chapter, which will help you prepare for your course, so you can get the most out of it.

Chapter 6: Academic Essays

How confident are you about your academic writing ability?

Check your score:

- 1–29: Your overall confidence level is low. You may be worried about your academic skills ability and what you will be required to do in written assignments. But don’t worry, many students feel like this when they start out on their academic journey. You will find that you are more able than you think. With practice, you will soon acquire and master key academic skills and your confidence and competence levels will improve quickly. It is excellent that you are aware of your concerns and you are ready to address these, and this book will help you do just that. We recommend that you work through each chapter systematically to maximise your skills development and build a solid foundation for your academic studies. You should re-visit the diagnostic regularly during the academic year to review your confidence levels in different areas of your writing, and also return to sections and tasks relevant to your immediate needs, to refresh and further enhance your skills base.

- 30–69: Your overall confidence level is moderate. You may have already developed some academic skills and perhaps feel reasonably confident about some areas and aspects of your studies. We recommend that you work through the chapter systematically, as you may need to revise and refresh your skills as you go along. While your skills knowledge and abilities may be adequate for ‘A’ Level or tertiary level study, they may not be sufficient or appropriate for your University assignments. This book will therefore provide you with the necessary nuts and bolts to up-skill, further enhance your confidence and improve your performance. Don’t forget to re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development, and re-visit sections that are relevant to your immediate needs.

- 70–100: Your confidence level is high to amazingly high! This may be because you have already developed a solid academic skills base to begin your studies. However, you should be aware that your confidence level might change when you begin your studies and you discover that your perceived skills level does not match your real-world abilities. We recommend that you go through the book and cherry pick the chapters, sections and tasks that you feel are most relevant to your needs, but we also recommend that you re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development and overall confidence levels, and regularly review relevant sections in the book, as your university career progresses.

Chapter 7: Lab Reports

How confident are you in your writing skills for a lab report?

Check your score

- 1–29: Your overall confidence level is low. You may be worried about your academic skills ability and what you will be required to do in written assignments. But don’t worry, many students feel like this when they start out on their academic journey. You will find that you are more able than you think. With practice, you will soon acquire and master key academic skills and your confidence and competence levels will improve quickly. It is excellent that you are aware of your concerns and you are ready to address these, and this book will help you do just that. We recommend that you work through each chapter systematically to maximise your skills development and build a solid foundation for your academic studies. You should re-visit the diagnostic regularly during the academic year to review your confidence levels in different areas of your writing, and also return to sections and tasks relevant to your immediate needs, to refresh and further enhance your skills base.

- 30–69: Your overall confidence level is moderate. You may have already developed some academic skills and perhaps feel reasonably confident about some areas and aspects of your studies. We recommend that you work through the chapter systematically, as you may need to revise and refresh your skills as you go along. While your skills knowledge and abilities may be adequate for ‘A’ Level or tertiary level study, they may not be sufficient or appropriate for your University assignments. This book will therefore provide you with the necessary nuts and bolts to up-skill, further enhance your confidence and improve your performance. Don’t forget to re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development, and re-visit sections that are relevant to your immediate needs.

- 70–100: Your confidence level is high to amazingly high! This may be because you have already developed a solid academic skills base to begin your studies. However, you should be aware that your confidence level might change when you begin your studies and you discover that your perceived skills level does not match your real-world abilities. We recommend that you go through the book and cherry pick the chapters, sections and tasks that you feel are most relevant to your needs, but we also recommend that you re-visit the diagnostic as your studies progress, to check your skills development and overall confidence levels, and regularly review relevant sections in the book as your university career progresses.

Chapter 8: Presentations

What makes a good presentation?

This speaker is successful for all of the reasons that these questions direct you to. To summarise, a good presentation is:

- well organised

- has a clear introduction

- includes some kind of ‘hook’ to grab the audience’s attention

- is clear with well-paced speaking (not too fast)

- includes pauses to help the audience process the ideas being presented

- will sound natural, because the speaker is referring to notes but NOT reading from notes

- includes supporting body language such as gestures, and facial expressions

- may include visual support, but this will be supporting and not a distraction.

How many features of a good presentation did you identify?

Are there any points that you feel more or less confident in yourself?

Chapter 9: Working in Groups

How comfortable are you working in a group?

How did you do?

- If your list of advantages is longer than your list of challenges, you’re probably ready to take advantage of group discussion!

- If your ‘challenges’ list looks longer, don’t worry – you’re in good company. Many people find group discussion difficult, but like all other communication it’s a skill you can learn. Pay special attention to this chapter.

- If your lists look about equal, make sure you give this chapter a close read. It won’t be long before your list of advantages is growing and you’re ready to tackle a group discussion!

Chapter 10: Taking Exams

How confident are you about writing exams?

Check your score:

- 25 and above: Congratulations! You’re clearly confident in your ability to prepare for and write effective exam answers, but this chapter can help enhance your skills with exams – so don’t skip it.

- 16–25: You’re definitely on your way. You understand what you need to do to do well in exams, but there’s always room to improve, so make sure you pay attention to the advice in this chapter.

- 10–15: You’re making a good start. This chapter gives you a chance to improve your skills with taking exams, helps you understand how to prepare effectively, and will help to boost your confidence even more.

- Below 10: This chapter will definitely help you feel more confident with the preparation for exams and how to maximise your success during exams.

Chapter 11: Writing Dissertations

How confident are you about writing your dissertation?

Check your score:

- 25 and above: Congratulations! You’re clearly confident in your ability to organise and write up your project or dissertation, but this chapter can help you check you have done the best job possible – so don’t skip it.

- 16–25: You’re definitely on your way. You understand what you need to do when preparing for and then writing up your dissertation, but there’s always room to improve, so make sure you pay attention to the advice in this chapter.

- 10–15: You’re making a good start. This chapter gives you tips and advice to help you from the earliest stage of your dissertation through to writing up your report, and will help to build your confidence further.

- Below 10: This chapter will definitely help you feel more confident with the preparation for your dissertation and with how to approach your writing.

Chapter 12: Creating Posters

How confident are you about creating posters??

Check your score:

- 25 and above: Congratulations! You’re clearly confident in your ability to design and write a poster, but this chapter can help you check you have done the best job possible – so don’t skip it.

- 16–25: You’re definitely on your way. You understand what you need to do when designing and writing a poster, but there’s always room to improve, so make sure you pay attention to the advice in this chapter.

- 10–15: You’re making a good start. This chapter gives you tips and advice on how to organise information in a poster, and how to ensure you consider design features, and by working through this chapter your confidence will be further boosted.

- Below 10: This chapter will definitely help you feel more confident with designing and writing posters.

Chapter 13: Reflective Essays

How confident are you about reflective writing?

Check your score:

- 25 and above: Congratulations! You’re clearly confident in your ability to write a reflective essay, but this chapter can help enhance your reflective skills – so don’t skip it.

- 16–25: You’re definitely on your way. You understand what you need to do when writing a reflective essay, but there’s always room to improve, so make sure you pay attention to the advice in this chapter.

- 10–15: You’re making a good start. This chapter gives you tips and advice on how to write reflectively and by working through this chapter your confidence will be further boosted.

- Below 10: This chapter will definitely help you feel more confident with writing reflective essays.

Chapter 14: Writing a Blog Post

- Academic blog posts can be different in style from other blog posts.

GT: they can be more formal than, for example, a travel blog, or a fashion blog, but this is not always the case. They also may include some expectation of the reader’s prior knowledge of the subject.

- A blog post uses a more informal style than an academic essay.

GT: the style of a blog post is usually more ‘chatty’ than academic writing, and can include informal features such as contractions (e.g. isn’t, don’t, wouldn’t etc), use of personal pronouns and personal opinion, questions, and informal punctuation such as exclamation marks.

- A blog post usually includes referencing in the same way as an academic essay.

GF: it is more likely to include hyperlinks to websites and other online sources such as social media or videos, than academic-style referencing.

- Readers of a blog post may not know about the subject being discussed in depth.

GT: this is a possibility with a blog post, that is less likely with an academic essay or paper. The reader may be interested to learn, but writer’s tend to assume that there is less background knowledge amongst their readership, and aim to use less subject-specific terminology and clarify situations and concepts.

- A blog post writer uses first person pronouns such as ‘I’.

GT: It is not always true, but it is an acceptable style in a blog to personalise your writing by using ‘I’ and ‘you’. It creates a more informal, ‘chatty’ style that may be more accessible to a non-expert audience.

- A blog post needs to be shorter than 500 words.

GF: Although blog posts are usually succinct and use shorter paragraphs than academic writing, there is no fixed length requirement. Most blog posts will probably be around 1000 words long, but this is not a ‘rule’.

Chapter 15: Taking a Critical Approach

How familiar are you with critical analysis?

Answer key

a Is it reliable / Is it commonly used? Sentence 3

b Who says this, is it your opinion or information from someone else? Sentence5

c What research has shown this? Sentence 4

d What situations? Sentence 2

e Is it? How certain are you of that? Sentence 1

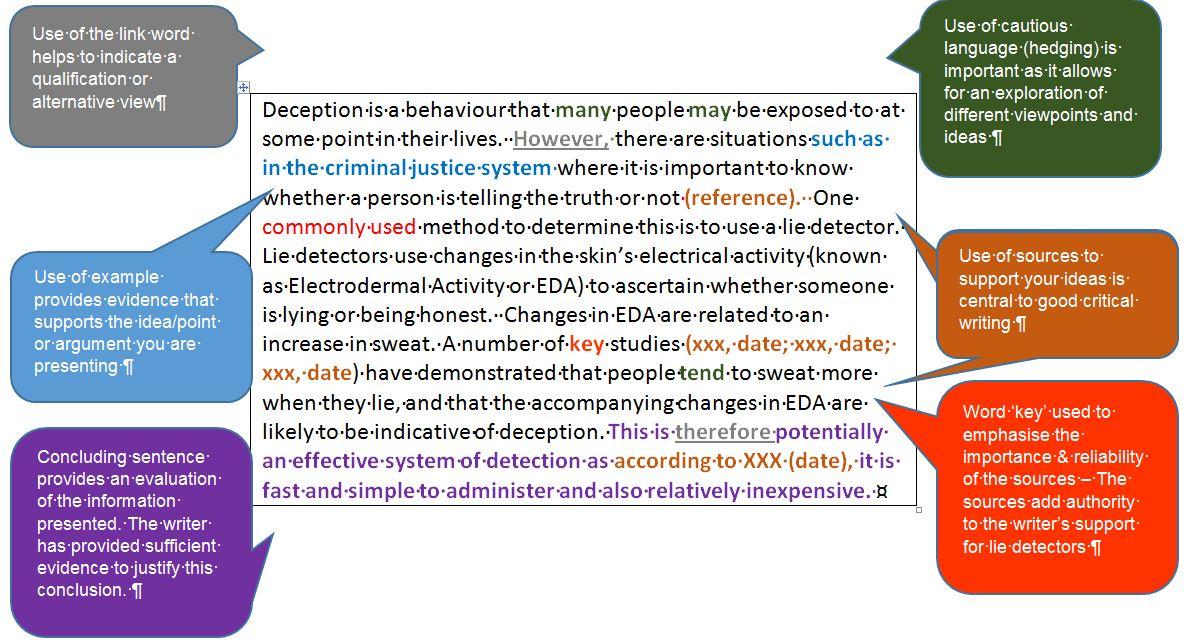

As a result of these questions, the text can be adapted to demonstrate a critical approach:

If you matched:

- all of the questions to the correct part of the text, congratulations! You have a very good understanding of the need for criticality in academic writing. But don’t skip this chapter; there is even more detail for you to learn.

- most of the questions to the correct part of the text, well done! You are on the right track and have an awareness of what to ask when taking a critical approach. Like most people, there’s always more to learn. You’ll pick up some tips in this chapter.

- only a few of the questions correctly: don’t worry. This chapter will help you improve your critical thinking skills. Critical thinking is an important feature of academic writing, and you should give yourself extra time in your assignment schedule to check for. We suggest you make good notes in this chapter.

Chapter 16: Writing with Clarity

How would you rate the clarity of your writing?

In this sample on psychology research, there were six problems with clarity. Here are the problems identified.

Infants of about 7 months (crawling age) are placed on a surface covered in a regular, chequered patterned material. First devised by Gibson and Walk (1960), this is a famous study known as the ‘visual cliff’. This material drapes over the edge of the surface and next to it is a sheet of transparent, safety glass. This study is limited as it cannot be used for infants who have not started crawling yet. Mothers beckoned their children towards them across the glass and over the “cliff”. This experiment investigated depth perception. Campos et al. (1981) divided pre-locomotor infants into two groups, with no locomotor experience and with 40 hours of experience in a baby walker. The heart rate dropped in the first group, whilst the heart rate increased in the second group when presented with the ‘visual cliff’. The heart rate increased is the mature response to steep drops. The studies by Gibson and Walk (1960) and Campos et al. (1981) and others indicate that infants can distinguish different depths before learning to crawl though don’t understand what the depth cues mean until about 7 months.

A Poor organisation – we need to know what we are reading about, AND the information does not flow between the two sentences.

B Difficult to remember what ‘this material’ refers to without looking back to the first sentence.

C These ideas seem to be in an illogical and unclear order.

D Does each group have both kinds of experience, or each group has a different kind of experience?

E Did the heart rate drop without being presented with the visual cliff?

F Unclear: should be either ‘The increased heart rate ...’ or ‘The heart rate increase ...’.

Here is an improved version with poorly organised sections rewritten for clarity.

This experiment investigated depth perception. A famous study first devised by Gibson & Walk (1960) known as the ‘visual cliff’ have infants of about 7 months (crawling age) placed on a surface that is covered in a regular, chequered, patterned material. This material drapes over the edge of the surface and next to the surface is a sheet of transparent, safety glass. Mothers beckoned their children towards them across the glass and over the “cliff”. This study is limited as it cannot be used for infants who have not started crawling yet. A following experiment by Campos et al. (1981) divided pre-locomotor infants into two groups, one with no locomotor experience and the second with 40 hours of experience in a baby walker. When presented with the ‘visual cliff’ the first group showed a drop in heart rate whilst the second group showed an increase in heart rate, the mature response to steep cliffs. These studies indicate that infants can distinguish different depths before learning to crawl though do not understand what the depth cues mean until about 7 months.

How did you score?

- If you underlined 6 sections, congratulations! Check the corrected sample to see if you are right. But there is even more for you to learn, so don’t skip this chapter.

- If you underlined 4 or 5, very good! You understand what makes writing clear. Like most people, there’s always more to learn. You’ll pick up some tips in this chapter.

- 2 or 3: You’re getting there. Clarity is an issue you should give yourself extra time in your assignment schedule to check for, and you can always ask friends to help. We suggest you make good notes in this chapter.

- If you found 1, this chapter will definitely help you get familiar with how to write clearly.

Chapter 17: Writing with Accuracy and Correct Use of Grammar

How would you rate the accuracy of your writing?

In the diagnostic paragraph about sleep needs, there were 14 problems to underline. Here are the authors’ answers:

Humans, like all animals, need sleep, along with food, water and oxygen, to survive. For humans sleep is a vital indicator of overall health and well-being. We spend up to one-third of our lives asleep, and the overall state of our sleep health remains an essential question throughout our lifespan. Most of us know that getting a good night’s sleep is important, but too few of us actually make those eight or so hours between the sheets a priority. For many of us with sleep debt, we’ve forgotten what being rested feels like.

To further complicate matters, stimulants like coffee and energy drinks, alarm clocks, and external lights—including those from electronic devices—interfere with our circadian rhythm or natural sleep/wake cycle. Other factors such as lifestyle and stress can make us lose sleep. Sleep needs vary across ages. Therefore, to determine how much sleep you need, it is important to assess not only where you fall on the sleep needs spectrum, but also to examine what lifestyle factors are affecting the quality and quantity of your sleep.

How did you score?

- 14: You may have found them all, congratulations! Check the corrected sample to see if you are right. But don’t skip this chapter; there is even more detail for you to learn.

- 10–13: Very good! You’ve got a sharp eye for spelling and grammar. Like for most people, there’s always more to learn. You’ll pick up some tips in this chapter.

- 5–9: You’re getting there. Accuracy is an issue you should give yourself extra time in your assignment schedule to check for. Don’t forget to ask friends to help! We suggest you make good notes in this chapter.

- 1–4: You’ve made a start – and this chapter is here to help you develop your ability to be accurate in your writing. Pay attention to the advice in the chapter and don’t forget to make detailed notes.

Chapter 18: Being Concise

How good are you at being succinct?

The authors were able to edit this sample down to 55 words without losing any meaning. Here is their version.

Participants had 20 seconds to fill in the words they associated with the words in the list from the appropriate block (A or B). Once the test was complete, participants wrote down their voting choice from the options. Participants remained anonymous with both the completed test form and voting choice placed in an unmarked envelope.

How did you score?

- Under 55: You don’t need a machete! Make sure you are preserving essential information.

- 55–60: You have sharp editing skills already.

- 60–65: You can spot fluff, but there’s still room to improve.

- 65–75: This chapter will be good practice for you, so we recommend special attention on the tasks.

Chapter 19: Writing in Academic Style

How confident are you with academic writing styles?

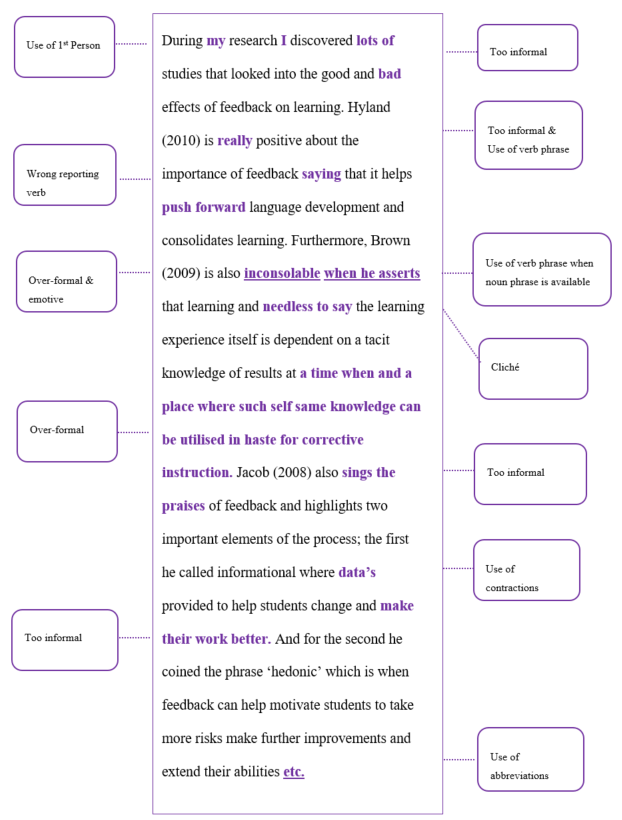

The authors have identified issues with informality, style and cliché. Here are the problems they found. See if they match what you thought was wrong with the academic style in the diagnostic.

This is one example of how to turn this paragraph into successful academic writing:

The nature, role, and importance of feedback in second language teaching pedagogy is well documented (Anderson 1982; Brophy 1981; Ferris 1995 & 2007; Hyland and Hyland 2006a & 2006b; Vgotsky 1978). Hyland and Hyland (2006a) argue that feedback is a critical element of language teaching as it helps to develop learning. Bruner (1970 cited by Falchikov 1995) goes further claiming that learning is “dependent on knowledge of results at a time when and a place where the knowledge can be used for correction” (p. 157). Jacobs 1974 (cited by Falchikov 1995) highlighted two important elements of feedback that make it vital to the learning process. The first element he described as ‘informational’, where data is provided to help students adapt and improve their work. The second he labelled as ‘hedonic’, where feedback can help influence the motivation of the student to take risks make further improvements and extend their abilities.

Chapter 20: Referencing with Accuracy

How well do you know the rules of referencing?

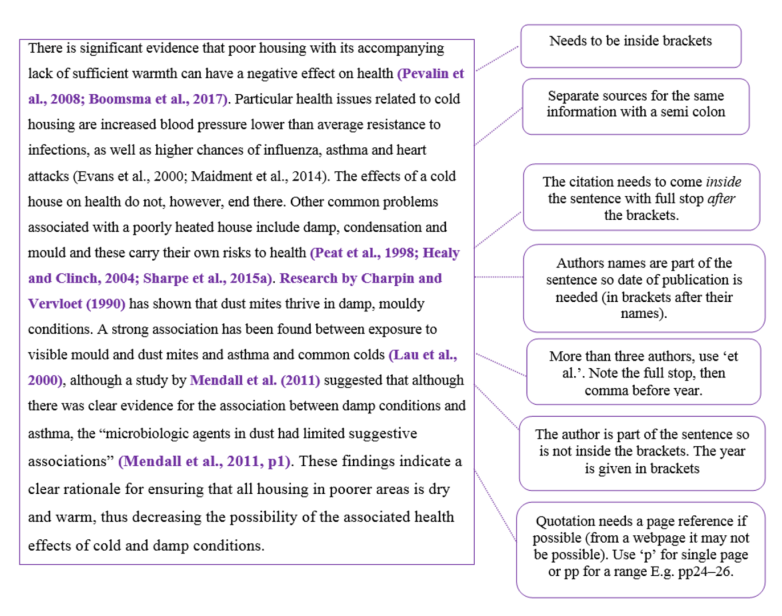

Your diagnostic should look like this:

There is significant evidence that poor housing with its accompanying lack of sufficient warmth can have a negative effect on health, Pevalin et al., 2008; Boomsma et al., 2017. Particular health issues related to cold housing are increased blood pressure, lower than average resistance to infections, as well as higher chances of influenza, asthma and heart attacks (Evans et al., 2000, Maidment et al., 2014). The effects of a cold house on health do not, however, end there. Other common problems associated with a poorly heated house include damp, condensation and mould and these carry their own risks to health. (Peat et al., 1998; Healy and Clinch, 2004; Sharpe et al., 2015) Research by Charpin and Vervloet has shown that dust mites thrive in damp, mouldy conditions. A strong association has been found between exposure to visible mould and dust mites and asthma and common colds (Lau, Illi, Sommerfeld, Niggemann, Bergmann, von Mutius, and Wahn, 2000), although a study by (Mendall et al., 2011), suggested that although there was clear evidence for the association between damp conditions and asthma, the “microbiologic agents in dust had limited suggestive associations” and therefore steps to improve health should focus on building design and energy efficiency (Mark J. Mendall et al., 2011). These findings indicate a clear rationale for ensuring that all housing in poorer areas is dry and warm, thus decreasing the possibility of the associated health effects of cold and damp conditions.

This shows you what the problems were and how to correct them:

How did you score?

How did you score?

- If you found all 7 issues, congratulations! But there’s still more you can learn about referencing, so don’t miss this chapter.

- If you found 4–6, you’ve clearly got a good understanding of referencing already! But you can still improve, so make good notes while you read this chapter.

- If you found 1–3, make sure you give this chapter a close read and take detailed notes about referencing accurately.

- If you couldn’t spot any, this chapter will definitely help you learn how to reference with accuracy.