An Introduction to Human Resource Management

Case Studies

Case studies exploring fascinating additional case studies from the author demonstrating HRM in practice around the world. From the internal vs. external candidate debate to employer branding abroad, learn how companies of all sizes approach different aspects of HRM.

- Workforce Planning in Practice at NHS London

In September 2008, NHS London published Workforce for London: A Strategic Framework, outlining the way in which the organisation was to address a number of key challenges facing health care in the capital over the coming decade. These include a rapidly growing population (predicted to equate to 600,000 additional users of health services over the next ten years) and the highly variable quality of health care provision, resulting in the highest rates of ‘consumer’ dissatisfaction in England. These challenges, along with a stated strategic objective to provide world-class health care for every Londoner, have significant implications for the size, shape and distribution of London’s health care workforce.

The current workforce

London’s complex health care system has the highest number of constituent NHS organisations in the UK and employs over 205,000 staff, 15.4 per cent of the total NHS workforce. It has some of the world’s leading medical centres of excellence which form a national and international hub for innovation in clinical care, research and education. However, the report also outlines a number of key staffing issues faced by NHS London, including:

- In London hospitals, the ratio of clinical staff to occupied beds varies from 0.9 to over 2.0.

- The lowest staffing levels are often in the areas with the greatest need – more GPs are in the south and west of London than in the more deprived east and north.

- London has more doctors (30.8 doctors per 10,000 population compared to an England average of 21.2) but fewer nurses (62.5 nurses per 10,000 population against an England average of 67.5) when compared with the rest of England.

- As a result of historic recruitment patterns and more staff delaying retirement, there is now a higher proportion of older staff in the workforce than ever before.

Health care has always attracted a large proportion of female workers, and there continue to be growing numbers of women in the medical workforce. It is anticipated that working hours per week in the medical workforce will reduce over the next ten years, reflecting a greater demand for flexible working arrangements by both men and women and the need for compliance with the European Working Time Directive by 2009, which imposes a maximum of 48 working hours per week. Advances in technology will also have a significant impact on the shape of London’s workforce through the creation of more centres with the technology and expertise to deliver highly specialised, complex care, and through the development of assisted technology, enabling care to be delivered closer to home. This will require the redesign of working patterns, the development of new skills and expertise and the opportunity to create new roles. London plays an important role both nationally and internationally in training and developing future health care professionals but suffers from high labour turnover and loss of key staff to other parts of the country. For example, London trains 29 per cent of UK medical undergraduates but over a third of these students do not work there after graduation. For nursing and midwifery, London’s share of students (18.3%) is in proportion to the number of staff employed (17.7%). However, it is believed that London exports qualified and experienced staff to the rest of England, as demonstrated by consistently higher vacancy rates.

Workforce for London: a strategic framework

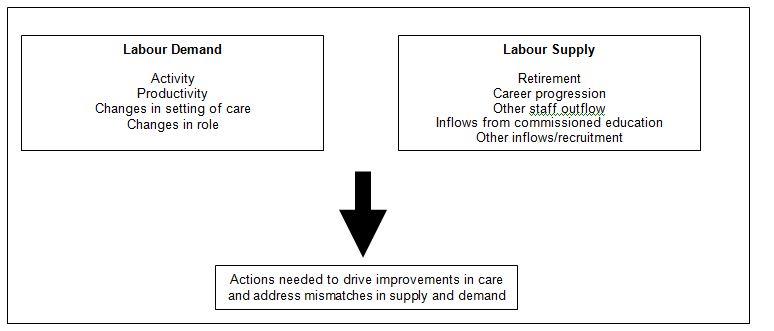

The purpose of the review which led to the strategic framework was to assess the impact of anticipated changes in health care needs, demographic trends, technology and patient and public expectations on the future size, shape and composition of London’s health care workforce and the changes required to how the organisation plans, trains, develops and deploys its employees. To assist in the workforce planning process, NHS London employed scenario modelling to provide insight into the strategic challenges ahead, and how these will affect the overall shape and size of London’s workforce.

Scenario modelling approach taken in Workforce for London

The resulting strategic framework identified a number of both quantitative and qualitative changes in the NHS workforce needed to meet the challenges of the coming decade. In broad terms, the strategic framework acknowledged the central role played by the workforce in high quality service delivery but identified that staff were not fully utilised (productivity levels of staff in London were lower than elsewhere in England). The review suggested that London’s NHS workforce will need to grow by between 4 and 23 per cent over the next ten years, dependent on the level of productivity delivered. The framework outlined three broad strands in how NHS London should respond to the demand and supply forecasting process.

The first focuses on the quantitative dimensions of the required workforce needed to increase productivity, to improve service quality and to address wider initiatives in the NHS regarding the delivery of care. The review indicated a need to develop new roles and new skills through increased targeted workforce development and investment. For example, the review advocates the development of broader sets of skills across the workforce. The review also suggests changes to where and how practitioners work, particularly through providing care closer to people’s homes. The review also suggests enhancing employment opportunities for Londoners to reduce turnover, and to develop a workforce more representative of the community it serves.

The second element focuses on the systems required to support this ‘new’ workforce. In particular, it stresses the importance of the effective integration of workforce planning, and educational investment, with service needs, particularly through the localisation (as far as possible) of workforce planning, tailored to meet the diverse needs of patients.

Finally, the framework proposes a number of changes to leadership processes, with a particular focus on fostering a climate of worker engagement and empowering frontline staff to ‘improve and develop the services they provide, creating new freedoms to innovate and provide the leadership for local change’. In response to recent staff surveys, NHS staff indicated that a positive relationship with staff tends to relate to improved performance and the framework indicates a desire to engender teamworking and ‘partnership’ across the organisation. The framework also indicates a need to develop excellent leaders at all levels of the organisation and to develop a pipeline of talent for chief executive and director roles across the capital.

Questions

- What are the pertinent factors that are shaping the supply and demand for medical practitioners in London over the coming decade? To what extent are these factors reasonably predictable?

- What responses to the workforce planning process are outlined in the case study?

- Why might the formal approach to workforce planning used by NHS London not necessarily be appropriate in many private sector organisations?

- How can HR planning contribute to the achievement of organisational objectives in all organisations?

- Resourcing the Call Centre at Tengo Ltd.

Tengo Ltd. is manufacturer of notebook computers. Since first entering the market in 2000 they have enjoyed rapid growth due to the ongoing popularity of their low-cost laptops aimed at the student market and the development of a range of higher-spec ‘business’ notebooks. Their products self in 30 countries across Europe and the Far East, although their main manufacturing operations, research and development and support functions (HR, finance, sales, marketing and IT) continue to be based in the UK where they employ over 500 members of staff. Given that Tengo trade exclusively over the Internet – they do not have retail outlets nor do not sell their products through high street retailers – The company’s customer contact centre provides a number of key functions: it is the customer point of contact for spares, accessories and extended product warranties; it provides technical support for existing customers; and, it is the channel for customer complaints; and, it fields enquiries about Tengo products. The contact centre was built three years ago on a greenfield site on the outskirts of a large town in the Midlands. There are a number of other customer contact centres situated nearby and, following a number of new employers locating to the region, competition for labour is intense, especially for those with prior call centre experience.

The workforce in the contact centre consists of a customer service director, a HR advisor, a call centre manager, 8 team supervisors and 95 contact centre advisors. Out of these 95 advisors, approximately 20 form the technical liaison team who deal with detailed technical questions and 10 members of staff working in the complaints department who also deal with some low-level technical enquiries. Twenty-five advisors deal with the ordering of spares and accessories and the remainder field enquiries about Tengo products. Tengo’s call centre is known locally to offer comparatively high pay, however a recent benchmarking study of local competitors found that other terms and conditions of employment were less favourable. In particular, advisors were required to work longer shifts than employees in other nearby centres and received less holiday entitlement and fewer opportunities for training and development.

Following a periodic HR planning exercise six months ago, the HR director (based in London) felt that Tengo’s rapid growth over the previous three years had led to overstaffing at the call centre, particularly amongst the customer service department. As a result, a programme of rationalisation and restructuring was undertaken resulting in the loss of 30 jobs in the contact centre. As a result, 18 workers were made redundant, with another 12 posts lost through ‘natural wastage’. Significant investment was also made in providing more effective and interactive online product support for customers, mainly to provide detailed technical advice. A customer satisfaction survey undertaken at the turn of the year rated satisfaction with after-sales customer service as poor and, subsequently, further investment was made into a new automated computer system which sought to standardise customer service, speed up response times and improve management’s ability to monitor service quality. It was also hoped that this would reduce training and development costs for new employees.

Following the restructuring, employee advisors were graded into three bands. Level 1 advisors, typically those dealing with customer complaints, were entry-level positions. The majority of advisors across most of the departments were Level 2. Advisors at Level 3 were mainly those dealing with detailed technical problems, commonly felt by the advisors to be the more interesting and desirable work, as well as having the best reward package. Among the technical support team, 16 of the 20 advisors had joined the company at a lower-level and had previously worked in at least one of the other areas of the contact centre. There was, however, greater ‘churn’ of employees in all other sections, particularly the complaints department in which 25 per cent of new recruits left within the first two months. Whilst prior to restructuring there had been a degree of movement between the departments, with workers often trained to undertake a variety of roles, the customer service director had decided to more clearly delineate the responsibilities of each department in the hope that customer service would be improved by encouraging advisors to specialise in particular areas.

Prior to the organisational restructuring, employee turnover was found to reflect both the industry and regional average. The customer service manager considers a certain level of turnover to be acceptable and even beneficial to the firm. Since the restructuring, however, labour turnover has increased by 10 per cent and a number of long-serving advisors have left the centre. Employee absence has risen significantly. Management took the decision to seek to tackle the recruitment problems in the technical support and team leader roles by focusing outside of the organisation in order to reduce training and development costs.

Task

Recent customer service feedback highlights growing customer dissatisfaction with after-sales support and complaint handling and the customer service director is under significant pressure to address these problems. He has asked you – the HR advisor – to explore the ‘people’ issues that might be contributing to poor service quality.

- What do you think the main causes of poor customer service quality at Tengo?

- How can you explain high labour turnover in the call centre?

- What information do you need to collect in orderly to understand and remedy turnover?

- How might this information be collected?

- Is turnover in the call centre likely to be universally dysfunctional?

- What changes would you make to HR practices and process within the call centre to address any identified problems?